Dreams often seem to play out like a low-budget arthouse film — bewildering plotlines; the same actor playing several roles; an abrupt end before a satisfying conclusion can be reached. Yet, according to one neuroscientist, the very absurdity of dreams might actually help us think more efficiently.

Whenever we learn something, the brain experiences a tug-of-war between memorization and generalization. We often need to retain the details of explicit facts, but if we over-memorize we lose the ability to apply the knowledge to other scenarios. “It’s like you’ve learned all of the specific answers for a test but none of the gist,” says Erik Hoel, a neuroscientist at Tufts University.

Generalizing Memories

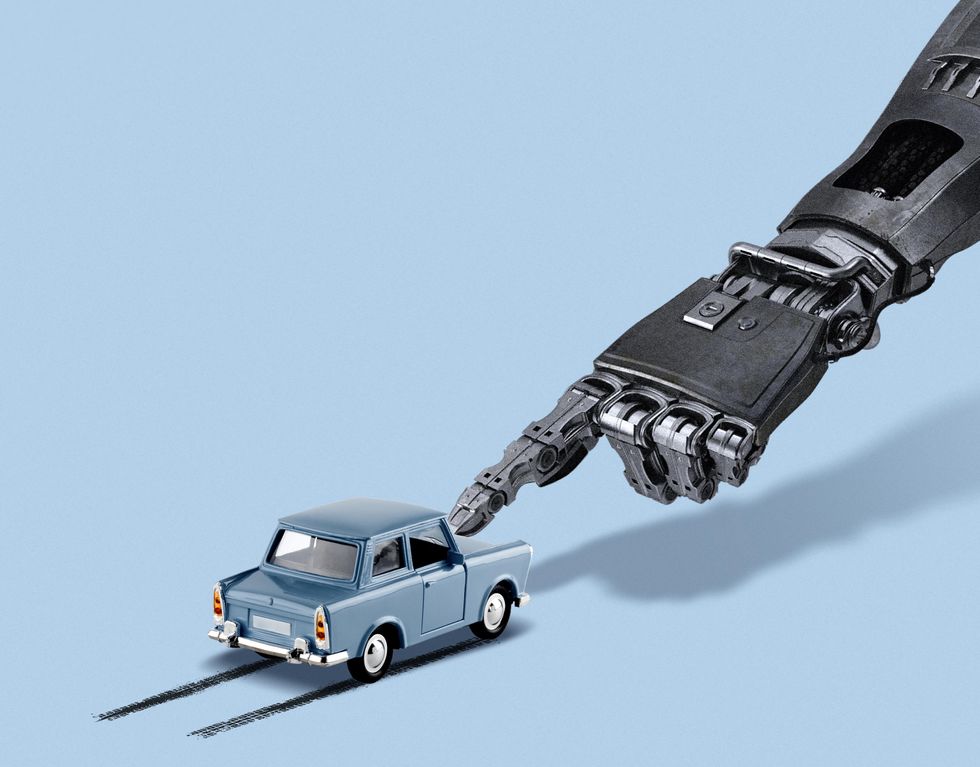

The same problem besets machine-learning researchers training deep-learning algorithms. For example, you might teach a neural network to recognize faces using a series of headshots. But this runs the risk of the computer overfitting to the dataset, memorizing the photos in the training data and ignoring any face it hasn’t previously seen.

Researchers prevent overfitting by removing detail and introducing noise via corrupting or warping the images. This teaches the network not to rely on rigid rules but instead learn the general outlines of faces.

Dreams may have evolved to combat what is essentially overfitting in the human mind, Hoel says. Rather than replaying the day’s events precisely as they happened, dreams throw up twisted versions of our thoughts and memories to prevent cognitive processes from becoming too inflexible.

Dreams also rub out detail, helping our brains to extract the “gist” from past experiences and apply it to other aspects of our lives. As Hoel points out, it’s rare to read books or compose text messages in dreams because the words would introduce too much detail, making the content less generalizable.

Generally, the easiest way to get someone to dream about something specific is to overtrain them on a particular task, Hoel says. Studies investigating whether dreams aid learning often have participants repeatedly play Tetris or navigate a 3D computerized maze.

Subjects who dreamed of the game improved the most, yet their dreams never involved performing the task itself. Instead, they saw floating shapes, mazelike caves or simply heard electronic music in their sleep. This suggests that dream-dependent learning doesn’t simply rely on activating memories, but rather extracting underlying concepts.

Such findings align with Hoel’s Overfitted Brain Hypothesis, which he believes best explains the absurdity of dreams — other theories either ignore the baffling nature of nighttime visions or explain it away as a quirky by-product. For instance, one theory proposes that dreams allow us to rehearse our responses to fear-inducing events, while another describes dreaming as a form of overnight therapy and claims it can remove the emotional charge attached to memories and help regulate mood.

The Utility of Odd Dreams

Researchers have long tried to explain why we experience odd dreams, says Robert Stickgold, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and co-author of When Brains Dream: Exploring the Science and Mystery of Sleep. “Freud said that the reason dreams are bizarre is that your ego brings up these repressed desires which need to be disguised to prevent the person from waking up,” he says.

As it turns out, dreams may help form connections between recent events and older, weakly related memories, suggest Stickgold and Antonio Zadra, a professor of psychology at the University of Montreal. The brain “monitors whether the narrative it constructs from these memories induces an emotional response,” Stickgold and Zadra wrote. If so, the unlikely connection is strengthened and we can ponder the association when we’re awake.

Why this is useful: Pairing memories with information lingering in the deepest recesses of our minds can help us make sense of past experiences, discover ingenious solutions to problems, and aid overall survival.

Stickgold thinks emotions might be crucial for signaling which connections between memories prove useful in our waking lives. In a 2001 Sleep study, he found that emotions cropped up in 74 percent of reports of REM sleep from nine subjects, and joy was most frequently mentioned.

And although most of our dreamy associations may not elicit an emotional reaction, a few might hit on profound, useful connections. “It’s like venture capitalists, who get a payoff one time in ten and it’s more than worth it,” he says.

Science owes a lot to the mysterious relationships conjured up by the dreaming brain, after all. Niels Bohr envisioned the nucleus of an atom in a dream about planetary orbits, while August Kekule conceived of the cyclical structure of benzene after dreaming of a snake swallowing its own tail. For the rest of us, our unconscious might not yield such large payouts, but we could still benefit from the surprising connections forged between memories.

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here