In 1912, Oskar von Miller, an electrical engineer and founder of the Deutsches Museum, had an idea: Could you project an artificial starry sky onto a dome, as a way of demonstrating astronomical principles to the public?

It was such a novel concept that when von Miller approached the Carl Zeiss company in Jena, Germany, to manufacture such a projector, they initially rebuffed him. Eventually, they agreed, and under the guidance of lead engineer Walther Bauersfeld, Zeiss created something amazing.

The use of models to show the movements of the planets and stars goes back centuries, starting with mechanical orreries that used clockwork mechanisms to depict our solar system. A modern upgrade was Clair Omar Musser’s desktop electric orrery, which he designed for the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962.

The projector that Zeiss planned for the Deutsches Museum would be far more elaborate. For starters, there would be two planetariums. One would showcase the Copernican, or heliocentric, sky, displaying the stars and planets as they revolved around the sun. The other would show the Ptolemaic, or geocentric, sky, with the viewer fully immersed in the view, as if standing on the surface of the Earth, seemingly at the center of the universe.

The task of realizing those ideas fell to Bauersfeld, a mechanical engineer by training and a managing director at Zeiss.

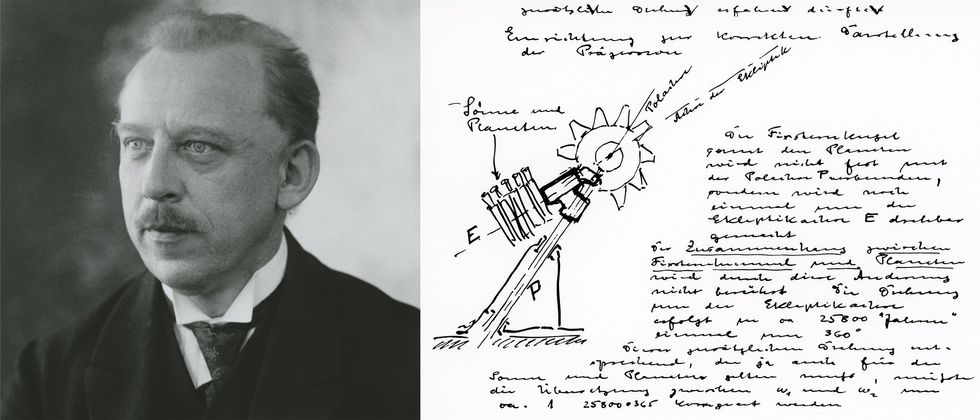

Zeiss engineer Walther Bauersfeld worked out the electromechanical details of the planetarium. In this May 1920 entry from his lab notebook [right], he sketched the two-axis system for showing the daily and annual motions of the stars.ZEISS Archive

Zeiss engineer Walther Bauersfeld worked out the electromechanical details of the planetarium. In this May 1920 entry from his lab notebook [right], he sketched the two-axis system for showing the daily and annual motions of the stars.ZEISS Archive

At first, Bauersfeld focused on projecting just the sun, moon, and planets of our solar system. At the suggestion of his boss, Rudolf Straubel, he added stars. World War I interrupted the work, but by 1920 Bauersfeld was back at it. One entry in May 1920 in Bauersfeld’s meticulous lab notebook showed the earliest depiction of the two-axis design that allowed for the display of the daily as well as the annual motions of the stars. (The notebook is preserved in the Zeiss Archive.)

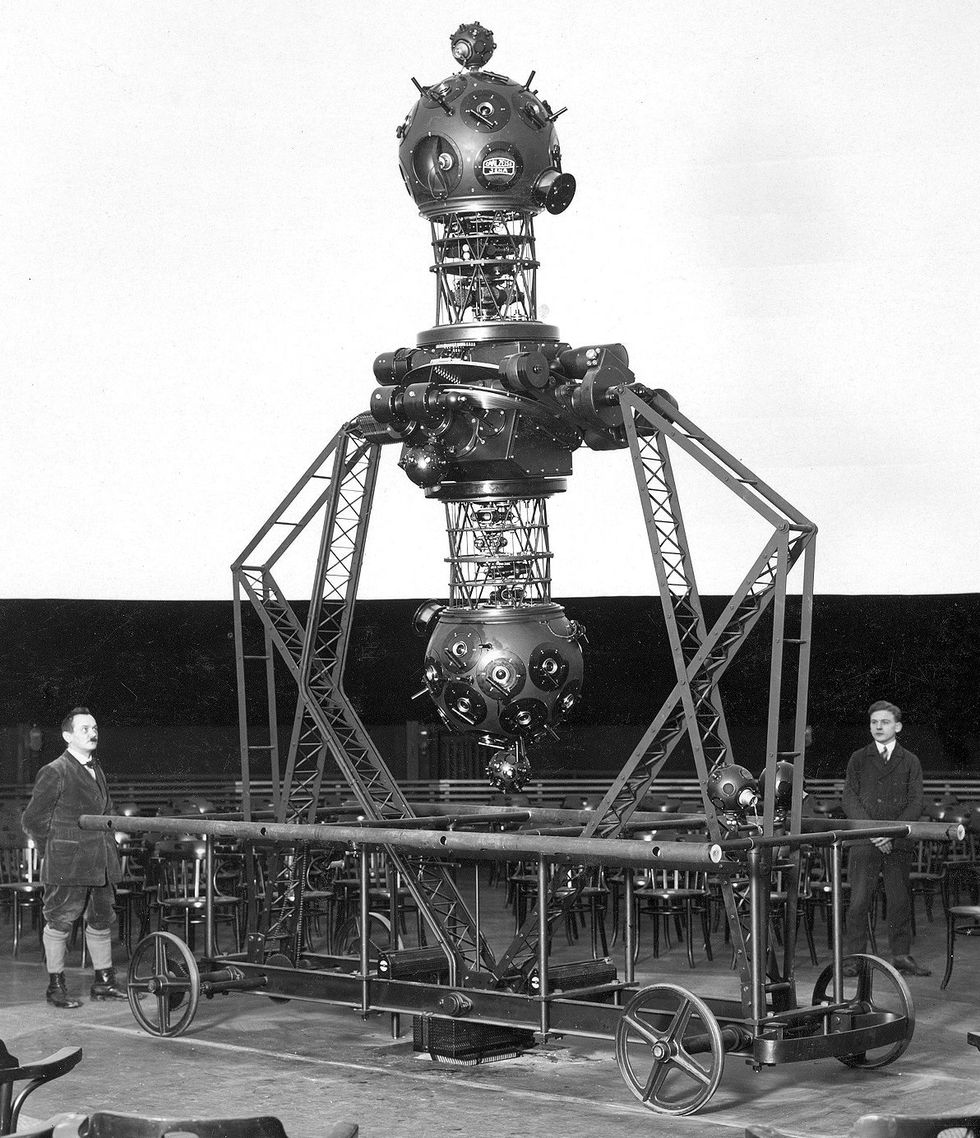

The planetarium projector was in fact a concatenation of many smaller projectors and a host of gears. According to the Zeiss Archive, a large sphere held all of the projectors for the fixed stars as well as a “planet cage” that held projectors for the sun, the moon, and the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The fixed-star sphere was positioned so that it projected outward from the exact center of the dome. The planetarium also had projectors for the Milky Way and the names of major constellations.

The projectors within the planet cage were organized in tiers with complex gearing that allowed a motorized drive to move them around one axis to simulate the annual rotations of these celestial objects against the backdrop of the stars. The entire projector could also rotate around a second axis, simulating the Earth’s polar axis, to show the rising and setting of the sun, moon, and planets over the horizon.

The Zeiss planetarium projected onto a spherical surface, which consisted of a geodesic steel lattice overlaid with concrete.Zeiss Archive

The Zeiss planetarium projected onto a spherical surface, which consisted of a geodesic steel lattice overlaid with concrete.Zeiss Archive

Bauersfeld also contributed to the design of the surrounding projection dome, which achieved its exactly spherical surface by way of a geodesic network of steel rods covered by a thin layer of concrete.

Planetariums catch on worldwide

The first demonstration of what became known as the Zeiss Model I projector took place on 21 October 1923 before the Deutsches Museum committee in their not-yet-completed building, in Munich. “This planetarium is a marvel,” von Miller declared in an administrative report.

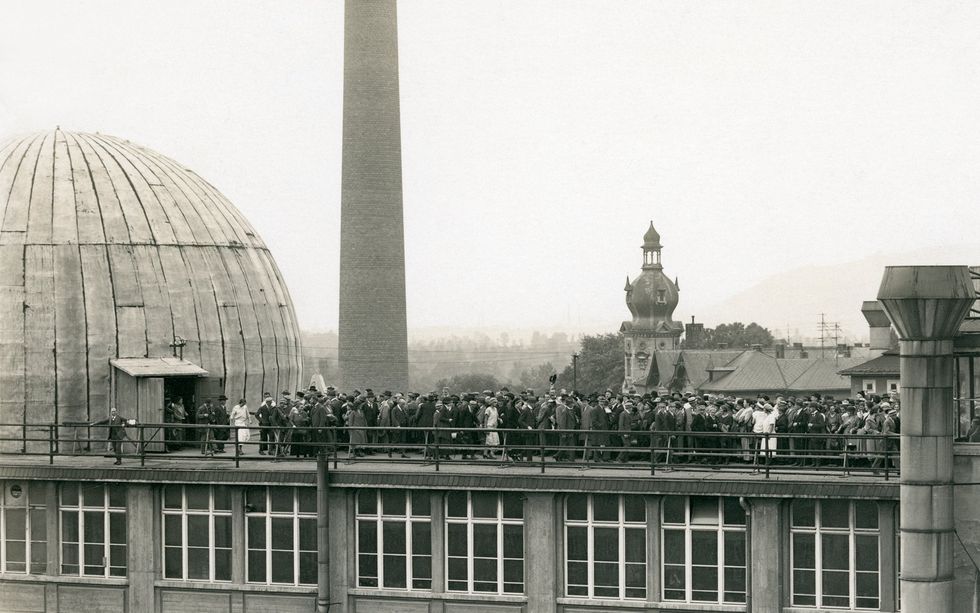

In 1924, public demonstrations of the Zeiss planetarium took place on the roof of the company’s factory in Jena, Germany.ZEISS Archive

In 1924, public demonstrations of the Zeiss planetarium took place on the roof of the company’s factory in Jena, Germany.ZEISS Archive

The projector then returned north to Jena for further adjustments and testing. The company also began offering demonstrations of the projector in a makeshift dome on the roof of its factory. From July to September 1924, more than 30,000 visitors experienced the Zeisshimmel (Zeiss sky) this way. These demonstrations became informal visitor-experience studies and allowed Zeiss and the museum to make refinements and improvements.

On 7 May 1925, the world’s first projection planetarium officially opened to the public at the Deutsches Museum. The Zeiss Model I displayed 4,500 stars, the band of the Milky Way, the sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Gears and motors moved the projector to replicate the changes in the sky as Earth rotated on its axis and revolved around the sun. Visitors viewed this simulation of the night sky from the latitude of Munich and in the comfort of a climate-controlled building, although at first chairs were not provided. (I get a crick in the neck just thinking about it.) The projector was bolted to the floor, but later versions were mounted on rails to move them back and forth. A presenter operated the machine and lectured on astronomical topics, pointing out constellations and the orbits of the planets.

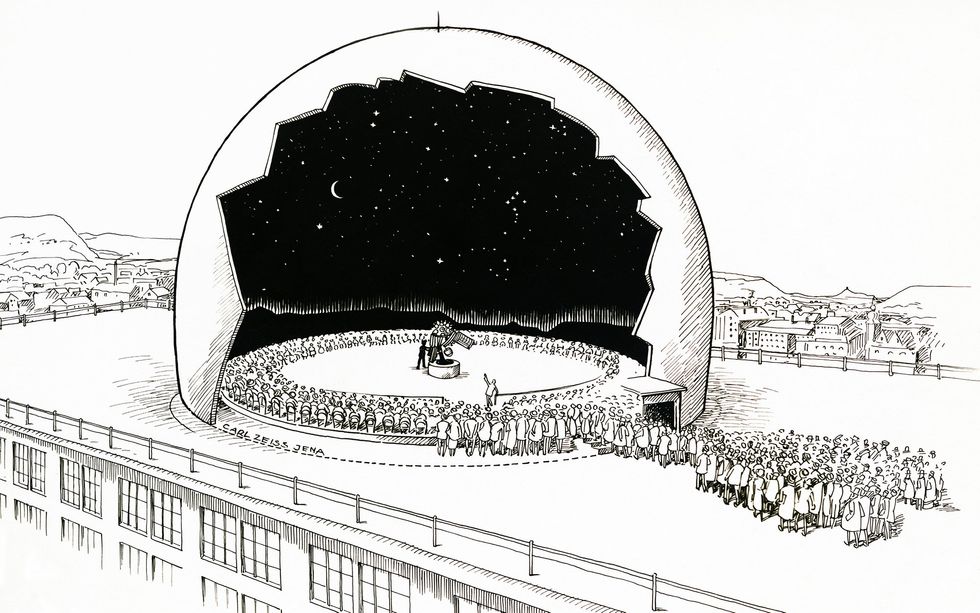

Word of the Zeiss planetarium spread quickly, through postcards and images.ZEISS Archive

Word of the Zeiss planetarium spread quickly, through postcards and images.ZEISS Archive

The planetarium’s influence quickly extended far beyond Germany, as museums and schools around the world incorporated the technology into immersive experiences for science education and public outreach. Each new planetarium was greeted with curiosity and excitement. Postcards and images of planetariums (both the distinctive domed buildings and the complicated machines) circulated widely.

In 1926, Zeiss opened its own planetarium in Jena based on Bauersfeld’s specifications. The first city outside of Germany to acquire a Zeiss planetarium was Vienna. It opened in a temporary structure on 7 May 1927 and in a permanent structure four years later, only to be destroyed during World War II.

The Zeiss planetarium in Rome, which opened in 1928, projected the stars onto the domed vault of the 3rd-century Aula Ottagona, part of the ancient Baths of Diocletian.

The first planetarium in the western hemisphere opened in Chicago in May 1930. Philanthropist Max Adler, a former executive at Sears, contributed funds to the building that now bears his name. He called it a “classroom under the heavens.”

Japan’s first planetarium, a Zeiss Model II, opened in Osaka in 1937 at the Osaka City Electricity Science Museum. As its name suggests, the museum showcased exhibits on electricity, funded by the municipal power company. The city council had to be convinced of the educational value of the planetarium. But the mayor and other enthusiasts supported it. The planetarium operated for 50 years.

Who doesn’t love a planetarium?

After World War II and the division of Germany, the Zeiss company also split in two, with operations continuing at Oberkochen in the west and Jena in the east. Both branches continued to develop the planetarium through the Zeiss Model VI before shifting the nomenclature to more exotic names, such as the Spacemaster, Skymaster, and Cosmorama.

The two large spheres of the Zeiss Model II, introduced in 1926, displayed the skies of the northern and southern hemispheres, respectively. Each sphere contained a number of smaller projectors.ZEISS Archive

The two large spheres of the Zeiss Model II, introduced in 1926, displayed the skies of the northern and southern hemispheres, respectively. Each sphere contained a number of smaller projectors.ZEISS Archive

Over the years, refinements included increased precision, the addition of more stars, automatic controls that allowed the programming of complete shows, and a shift to fiber optics and LED lighting. Zeiss still produces planetariums in a variety of configurations for different size domes.

Today more than 4,000 planetariums are in operation globally. A planetarium is often the first place where children connect what they see in the night sky to a broader science and an understanding of the universe. My hometown of Richmond, Va., opened its first planetarium in April 1983 at the Science Museum of Virginia. That was a bit late in the big scheme of things, but just in time to wow me as a kid. I still remember the first show I saw, narrated by an animatronic Mark Twain with a focus on the 1986 visit of Halley’s Comet.

By then the museum also had a giant OmniMax screen that let me soar over the Grand Canyon, watch beavers transform the landscape, and swim with whale sharks, all from the comfort of my reclining seat. No wonder the museum is where I got my start as a public historian of science and technology. I began volunteering there at age 14 and have never looked back.

Part of a continuing serieslooking at historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the May 2024 print issue as “A Planetarium Is Born.”

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here