Erik Johnson didn’t know his grandma, was a game industry icon. But most of the video game industry didn’t know either.

Mabel Addis, (Johnson’s “gaga”, as he puts it) created The Sumerian Game with IBM in 1964, and in doing so, became the first narrative designer. She also created one of the first educational video games, and one of the first with a strong roleplaying component to the play experience. Johnson most recently accepted the Pioneer Award on behalf of his grandma at the 2023 Game Developers Choice Awards. Until this year’s Game Developers Conference, he had no idea how significant Addis’ contributions were to the game industry.

“You don’t realize how much is devoted to something,” he said in a recent conversation. “You see these conferences and lines wrapped about the building; your whole world opens up to a thing you had no idea about.”

Addis’ absence of industry recognition, and eventual elevation, is similar to Jerry Lawson, credited with inventing the cartridge. Lawson first attended GDC in 2011 as an invited guest from the International Game Developer’s Association; he passed away several months later. Since then, he’s become a prominent icon in the game design history.

After Lawson’s passing, numerous foundations have been established in his name. Including the IGDA Foundations’ Jerry A. Lawson award for Achievement in Game Development and the Blacks in Gaming Awards’ Jerry Lawson Lifetime Achievement Award. Jerry was most recently celebrated publicly in a Google Doodle last December.

There are many reasons why Addis and Lawson deserve these accolades. However, it does raise important questions about how the game industry remembers its greatest contributors. Why did it take so long to acknowledge their work? What needs to happen to discover and elevate these people. It takes effort from people in academia, the video game industry, and even in museum and curatorial spaces to highlight these industry icons.

Elevating the work of Lawson, Addis, and beyond

Some of the reasons these people haven’t been discovered is that they weren’t considered members of the video game industry. Mabel Addis was working with IBM, but was primarily a teacher and member of her local community. Game design wasn’t her career. Lawson was an engineer at Fairchild, but his contributions to the industry existed before games had a public identity beyond Nolan Bushnell and Atari.

Additionally, many people in the industry treat work for years as a career without any public-facing role. Lawson wasn’t a prominently discussed figure until relatively recently. He had previously spoken at game history and early computing events, but didn’t make many appearances at industry-focused shows. This led to his absence from more mainstream game history conversations.

Carl Varnado, Chair of the IGDA Blacks in Gaming SIG and member of the Blacks in Gaming Foundation, works on highlighting figures like Lawson.

“There are these really amazing people that have worked in these companies for 20 years, Varnado said. Even if these developers were highly respected by their employers “they’ve been by themselves in isolation”

Varnado’s work with the Blacks in Gaming Awards focuses on highlighting black industry veterans that might not have been in the public eye. Most recently, Josiane Valverde was honored with the Jerry A. Lawson Lifetime Achievement Award after working at Ubisoft for 35 years. Ubisoft’s decision to feature the award on its website helps companies show that people of color have always been a part of their history, says Varnado. “You putting visibility adds recognition, and helps all people to see that being in the industry is not an anomaly,” he added.

Finding the people that made history takes hard work

Varnado’s work and the Lawson Lifetime Achievement Award focus on highlighting people who have been in the industry a long time, but whose work may never have been showcased outside of the company. Their persistence is what makes them significant, given how volatile the game industry can be.

History moves forward, and it requires introspection and recollection to realize that the present day will be recorded as history. “We’re the first generation of gamers who are…raising children, so we think about gaming differently,” Varnado said. “We think about it as an industry and a habit and a passion; so there’s history we’re looking for. I don’t think we were 20 years ago.”

For significant industry members lost in history, however, it takes a different historical approach to recover their memory. Names like Addis’ might pop up while a researcher is looking for other information, and drive them to dig into completely different topics. Finding new information (or noting the lack of information), and being armed with your own cultural and contextual knowledge of history can help highlight why these names might need to be better remembered.

That process still involves a lot of time and effort. The Sumerian Game might exist in IBM’s archives, but isn’t playable today. Addis’ design lineage, however, can be traced through some of the largest works of 1970s nonfiction-based computer games.

Devin Monnens, instructional designer at Seminole State College in Florida and one of the earliest people to highlight Addis’ work, spent ten years looking through early PC history before discovering Addis’ influence. Her game inspired Hamurabbiwhich later inspired Santa Paravia in Fiumacciowhich influenced Don Daglow when he designed Utopia. Hamurabbi was also played by Jim Storer, creator of Lunar Lander.

Monnens explained that historic flavor of thes older games may be what inspired later creators to take influence from the depths of history. “If Hamurabbi hadn’t been there providing a historical context to create a simulation,” he said, “what game would [future developers] have made? Would [they] have picked that scenario if they hadn’t been using Hammurabi as one of their examples?”

Additionally, It takes interested outsiders who want to share these stories to elevate these voices – both Johnson and Monnens say Kate Willaert’s article on Addis was the first significant article that highlighted her contributions to games. Without it, she probably would not have received the Pioneer Award.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

JP Dyson, Director of the International Center of Digital Games and Vice President of Exhibits of the Strong Museum of Play, finds plenty of historical revelations when looking for unknown icons of games history. One of the advantages Addis’ legacy has is that it’s connected to design fields such as early computing and educational games. While there wasn’t a strong record, there was a lineage that could be traced.

“When access to computer power was limited, you might play [games] at school. It’s an area that often gets ignored compared to classic AAA titles.” This explains why there are so many games that stick with people from an early age. This was their one entry point to technology, therefore the games like Oregon Trail, Freddy Fish or Bailey’s Book House can become monumental, if understated, works of game design. Dyson also says that the early internet is full of unknowns that made a significant mark on history.

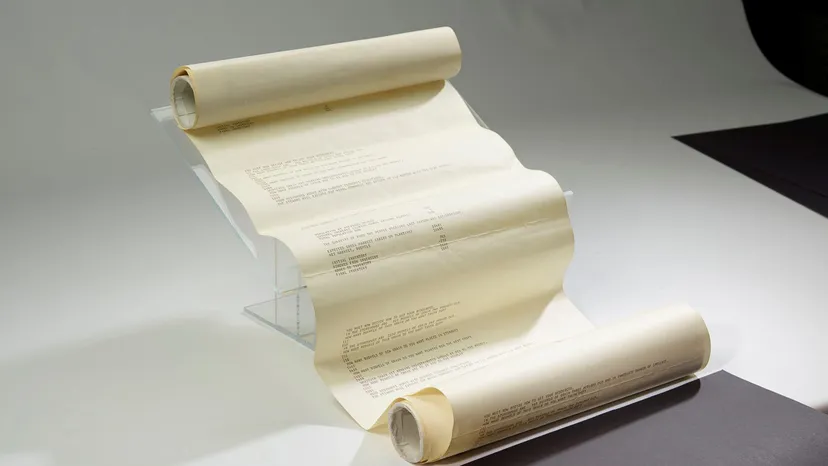

Addis and Lawson will both be highlighted in The Strong’s upcoming exhibits, one focusing on how story intersects with games, and one highlighting industry icons. Addis’ exhibit will include a printout of play from The Sumerian Gameoriginally printed on connected dot matrix paper.

“I think it’s the most wonderful artifact,” Dyson said. “It’s a game about Ancient Sumer and they’re like these scrolls.” Included in the display will be the slides used to help convey theme and narrative while playing the game. Both exhibits are a part of the Strong’s recent 90,000 square foot expansion.

Seeing family members honored as icons is an unforgettable experience. Nothing is more amazing to Johnson than seeing his grandma honored. She was the first in a long line of meaningful moments in game design. Her contributions stand as the start of new design techniques. Unlike being a top seller, or holding a world record, Addis’ contributions can’t be overshadowed. “This isn’t the high jump,” he said, comparing her work to a record that could simply be surpassed by a future athlete. “You can’t take that away.”

The history of video games is told by those who were approachable and in the public eye. This means that those who talked about games are those that became the first industry icons. However, for many reasons, there are those that didn’t have that platform and have become forgotten.

It’s up to the efforts of historians, museums, and other people in the industry to make sure we elevate the marginalized icons that history forgot.

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here

/images/2f890f29/3267/4f2f/91a1/6ccf6dbec931.jpg)