Using the Very Large Telescope, astronomers have discovered a stellar-mass black hole in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a neighbor galaxy to our own.

A stellar-mass black hole in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a neighbor galaxy to our own, has been found by a team of international experts, renowned for debunking several black hole discoveries. “For the first time, our team got together to report on a black hole discovery, instead of rejecting one,” says project leader Tomer Shenar. Furthermore, they discovered that the star that gave rise to the black hole vanished with no trace of a massive explosion. Six years of observations with the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT) resulted in the finding.

The black hole police, a team of astronomers known for debunking black hole discoveries, reported finding a “needle in a haystack.” After searching nearly 1000 stars outside our galaxy, they found that one of them has a stellar-mass black hole as a companion. This short video summarizes the discovery. Credit: ESO

“We identified a ‘needle in a haystack’,” says Tomer Shenar who started the study at KU Leuven in Belgium[1] and is now a Marie-Curie Fellow at Amsterdam University, the Netherlands. Other similar black hole candidates have been proposed before, however, the team says that this is the first ‘dormant’ stellar-mass black hole to be definitively found beyond our galaxy.

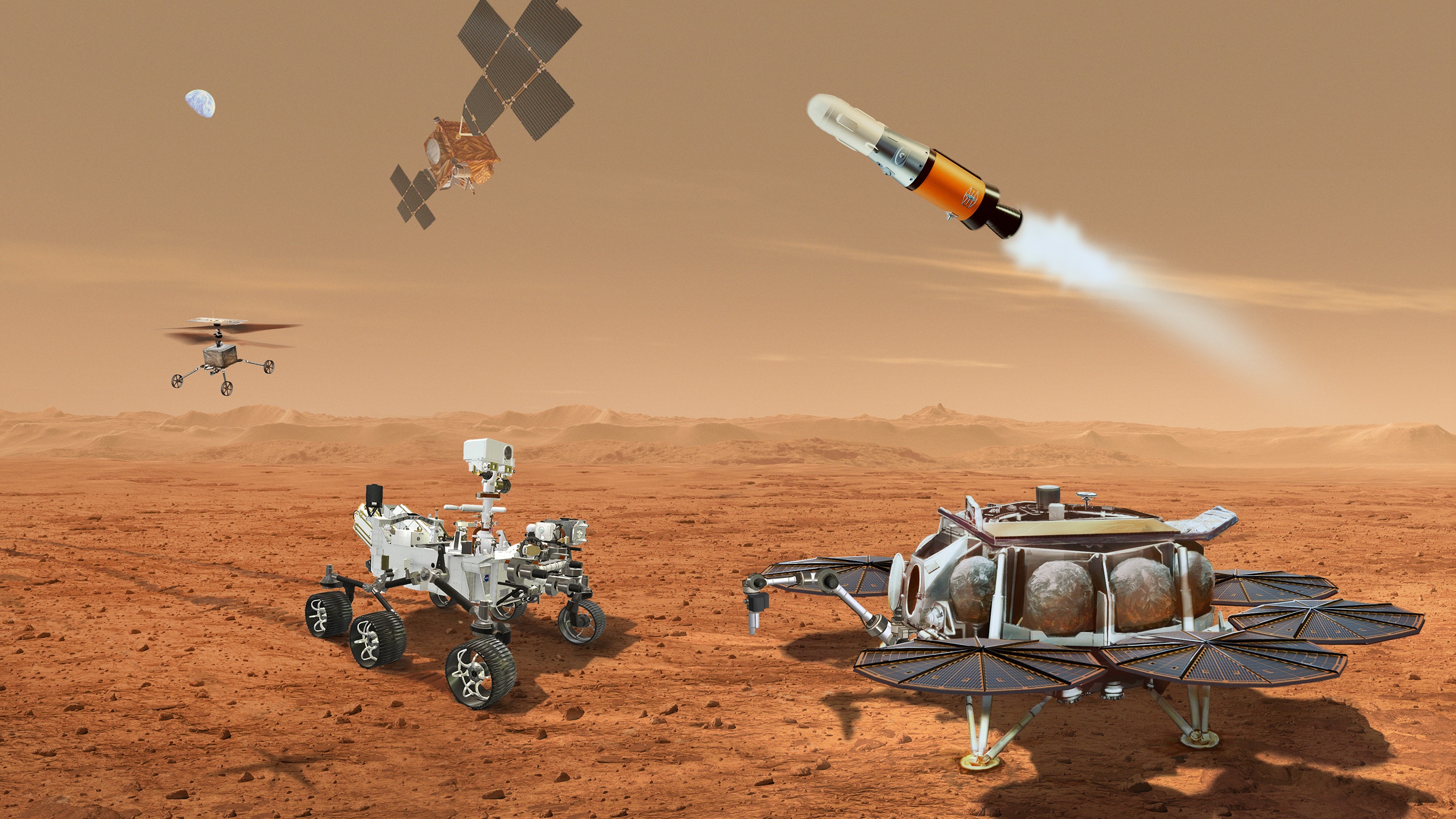

This artist’s impression shows what the binary system VFTS 243 might look like if we were observing it up close. The system, which is located in the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud, is composed of a hot, blue star with 25 times the Sun’s mass and a black hole, which is at least nine times the mass of the Sun. The sizes of the two binary components are not to scale: in reality, the blue star is about 200,000 times larger than the black hole.

Note that the ‘lensing’ effect around the black hole is shown for illustration purposes only, to make this dark object more noticeable in the image. The inclination of the system means that, when looking at it from Earth, we cannot observe the black hole eclipsing the star. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

When large stars approach the end of their lifetimes and collapse under their own gravity, stellar-mass black holes arise. In a system of two stars revolving around each other, which is known as a binary, this process leaves behind a black hole in orbit with a luminous companion star. If a black hole does not emit high levels of X-ray radiation, which is how such black holes are generally found, it is said to be ‘dormant.’

“It is incredible that we hardly know of any dormant black holes, given how common astronomers believe them to be,” explains co-author Pablo Marchant of KU Leuven. The newly discovered black hole has at least nine times the mass of our Sun and is orbiting a hot, blue star with a mass 25 times that of our Sun.

Since they have little interaction with their environment, dormant black holes are particularly difficult to detect. “For more than two years now, we have been looking for such black-hole-binary systems,” says co-author Julia Bodensteiner, a research fellow at ESO in Germany. “I was very excited when I heard about VFTS 243, which in my opinion is the most convincing candidate reported to date.”[2]

Glowing brightly about 160,000 light-years away, the Tarantula Nebula is the most spectacular feature of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to our Milky Way. This image from VLT Survey Telescope at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile shows the region and its rich surroundings in great detail. It reveals a cosmic landscape of star clusters, glowing gas clouds, and the scattered remains of supernova explosions. Credit: ESO

To find VFTS 243, nearly 1000 massive stars in the Tarantula Nebula region of the Large Magellanic Cloud were searched by the collaboration, which was looking specifically for the ones that could have black holes as companions. Since so many alternative possibilities exist, it is extremely difficult to definitively identify these companions as black holes.

“As a researcher who has debunked potential black holes in recent years, I was extremely skeptical regarding this discovery,” says Shenar. The skepticism was shared by co-author Kareem El-Badry of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in the USA, whom Shenar calls the “black hole destroyer.” “When Tomer asked me to double check his findings, I had my doubts. But I could not find a plausible explanation for the data that did not involve a black hole,” explains El-Badry.

This composite image shows the star-forming region 30 Doradus, also known as the Tarantula Nebula. The background image, taken in the infrared, is itself a composite: it was captured by the HAWK-I instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA), shows bright stars and light, pinkish clouds of hot gas. The bright red-yellow streaks that have been superimposed on the image come from radio observations taken by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), revealing regions of cold, dense gas which have the potential to collapse and form stars. The unique web-like structure of the gas clouds led astronomers to the nebula’s spidery nickname.

Credit: ESO, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Wong et al., ESO/M.-R. Cioni/VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey. Acknowledgment: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit

The discovery also allows the team a unique view into the processes that accompany the formation of black holes. Astronomers believe that a stellar-mass black hole forms as the core of a dying massive star collapses, but it remains uncertain whether or not this is accompanied by a powerful supernova explosion.

“The star that formed the black hole in VFTS 243 appears to have collapsed entirely, with no sign of a previous explosion,” explains Shenar. “Evidence for this ‘direct-collapse’ scenario has been emerging recently, but our study arguably provides one of the most direct indications. This has enormous implications for the origin of black-hole mergers in the cosmos.”

In this video, we get to fly out from our home galaxy and into the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a satellite galaxy to the Milky Way. The LMC is the home of one of the brightest known nebulae, the Tarantula Nebula, which was discovered in the mid-18th century. The Tarantula Nebula hosts the binary system VFTS 243, where this video eventually ends. The system might seem like a lone hot blue star, but the other component is in fact invisible to us: a black hole, weighing at least nine times the mass of our Sun, and about 200 000 times smaller than its stellar companion.

The black hole in VFTS 243 was found using six years of observations of the Tarantula Nebula by the Fibre Large Array Multi Element Spectrograph (FLAMES) instrument on ESO’s VLT.[3]

Despite the nickname ‘black hole police’, the team actively encourages scrutiny, and hopes that their work, published today (July 18, 2022) in Nature Astronomy, will enable the discovery of other stellar-mass black holes orbiting massive stars, thousands of which are predicted to exist in Milky Way and in the Magellanic Clouds.

“Of course I expect others in the field to pore over our analysis carefully, and to try to cook up alternative models,” concludes El-Badry. “It’s a very exciting project to be involved in.”

This animation shows what the binary system VFTS 243 might look like if we were observing it up close and at an inclination different from that we see from Earth. The system is composed of a hot, blue star with 25 times the Sun’s mass and a black hole, which is at least nine times the mass of the Sun. The sizes of the two binary components are not to scale: in reality, the blue star is about 200,000 times larger than the black hole. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

Notes

- The work was conducted in the team led by Hugues Sana at KU Leuven’s Institute of Astronomy.

- A separate study led by Laurent Mahy, involving many of the same team members and accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics, reports on another promising stellar-mass black hole candidate, in the HD 130298 system in our own Milky Way galaxy.

- The observations used in the study cover about six years: they consist of data from the VLT FLAMES Tarantula Survey (led by Chris Evans, United Kingdom Astronomy Technology Centre, STFC, Royal Observatory, Edinburgh; now at the European Space Agency) obtained from 2008 and 2009, and additional data from the Tarantula Massive Binary Monitoring program (led by Hugues Sana, KU Leuven), obtained between 2012 and 2014.

More information

Reference “An X-ray quiet black hole born with a negligible kick in a massive binary of the Large Magellanic Cloud” 18 July 2022, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-022-01730-y

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement numbers 772225: MULTIPLES) (PI: Sana).

The team is composed of T. Shenar (Institute of Astronomy, KU Leuven, Belgium [KU Leuven]; Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands [API]), H. Sana (KU Leuven), L. Mahy (Royal Observatory of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium), K. El-Badry (Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, Cambridge, USA [CfA]; Harvard Society of Fellows, Cambridge, USA; Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany [MPIA]), P. Marchant (KU Leuven), N. Langer (Argelander-Institut für Astronomie der Universität Bonn, Germany, Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn, Germany [MPIfR]), C. Hawcroft (KU Leuven), M. Fabry (KU Leuven), K. Sen (Argelander-Institut für Astronomie der Universität Bonn, Germany, MPIfR), L. A. Almeida (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, Brazil; Universidade do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte, Mossoró, Brazil), M. Abdul-Masih (ESO, Santiago, Chile), J. Bodensteiner (ESO, Garching, Germany), P. Crowther (Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Sheffield, UK), M. Gieles (ICREA, Barcelona, Spain; Institut de Ciències del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain), M. Gromadzki (Astronomical Observatory, University of Warsaw, Poland [Warsaw]), V. Henault-Brunet (Department of Astronomy and Physics, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Canada), A. Herrero (Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain [IAC]; Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain [IAC-ULL]), A. de Koter (KU Leuven, API), P. Iwanek (Warsaw), S. Kozlowski (Warsaw), D. J. Lennon (IAC, IAC-ULL), J. Maíz Apellániz (Centro de Astrobiología, CSIC-INTA, Madrid, Spain), P. Mróz (Warsaw), A. F. J. Moffat (Department of Physics and Institute for Research on Exoplanets, Université de Montréal, Canada), A. Picco (KU Leuven), P. Pietrukowicz (Warsaw), R. Poleski (Warsaw), K. Rybicki (Warsaw and Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel), F. R. N. Schneider (Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies, Heidelberg, Germany [HITS]; Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany), D. M. Skowron (Warsaw), J. Skowron (Warsaw), I. Soszynski (Warsaw), M. K. Szymanski (Warsaw), S. Toonen (API), A. Udalski (Warsaw), K. Ulaczyk (Department of Physics, University of Warwick, UK), J. S. Vink (Armagh Observatory & Planetarium, UK), and M. Wrona (Warsaw).

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here