OAKLAND, California – For three years, Bertha Embriz, of San Francisco, has lived without health insurance, skipping yearly checkups, and now trying not to chew on one side to avoid the pain of a broken tooth. As an immigrant without legal status, the 58-year-old unpaid caregiver knew that California’s Medicaid program was not for her.

But that changed in May, when California expanded Medi-Cal, its low-income Medicaid program, to adults 50 and older, regardless of immigration status. The problem was that Embriz didn’t realize she might be eligible until she went to a community meeting in San Francisco.

“I heard they were giving Medi-Cal to people over 50, but I didn’t know you didn’t have to be” in the country legally, said Embriz, who is waiting for his application to be processed. “Thank God I haven’t had any emergencies.”

As of October, the most recent month for which data is available, more than 300,000 immigrant seniors who do not have legal residency had enrolled in full Medi-Cal30% more than the state’s original projection.

State health officials, who had based their estimate on the number of people enrolled in a limited form of Medi-Cal that covers only emergency medical services, don’t know how many additional older Californians are eligible, said Tony Cava, a spokesman for the Department of Health Services. of State Medical Care.

Now, some counties have hired a small army of community workers and health educators to enroll as many immigrant seniors as possible. These workers visit senior centers, churches, English classes, immigration offices, markets and community events, hoping to find people like Embriz who may not be aware of their new eligibility.

In Alameda County, Juan Ventanilla, an expert on the Medi-Cal program, said the social services agency is using existing state grants to partner with eight established community organizations to help get the word out about the expansion, and to people register.

He said the workers specialize in “helping the county’s most vulnerable gain access to healthcare.”

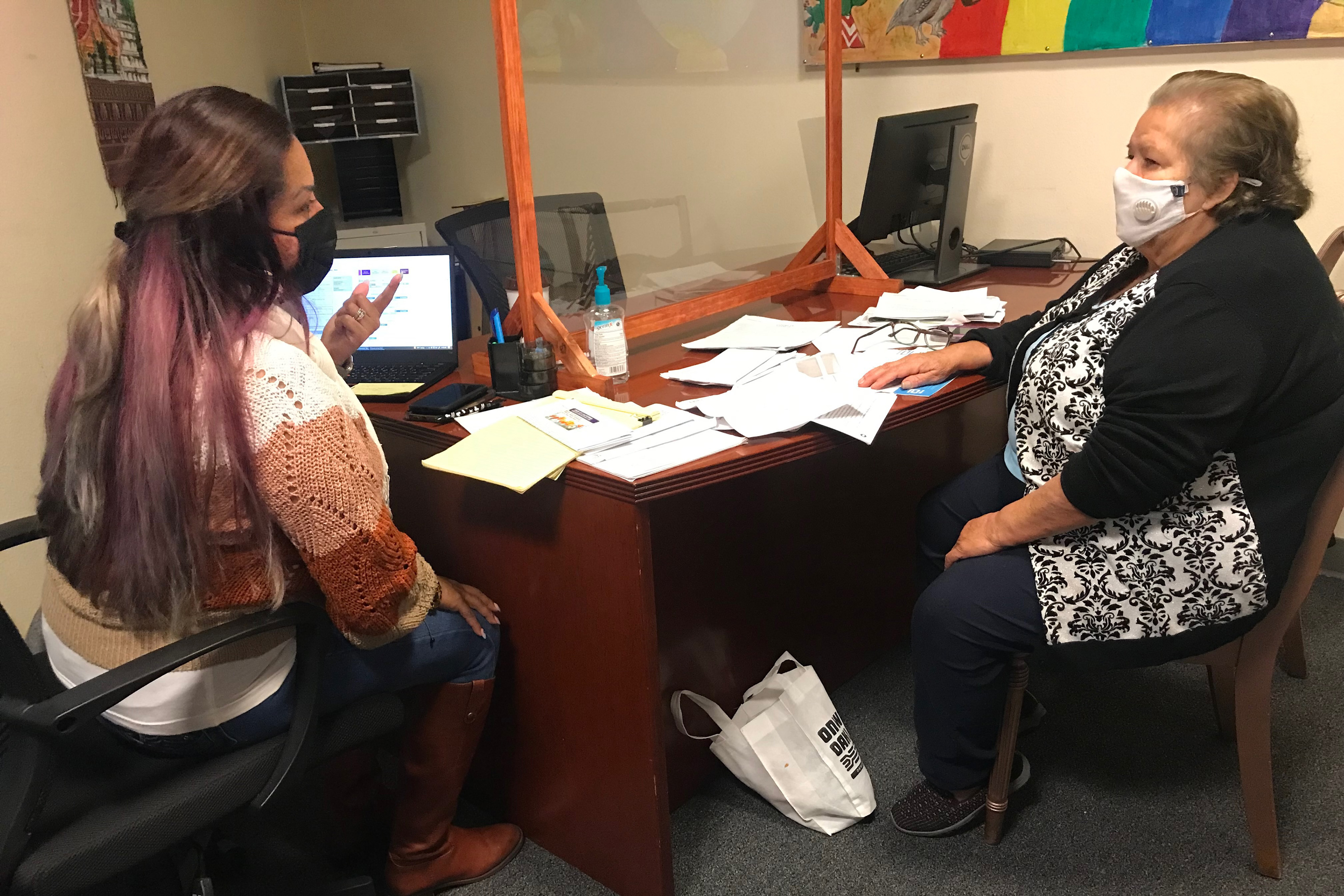

Among them are Ana Hernández and Bertha Ortega, from Casa Che, a community health education center in the Fruitvale neighborhood of Oakland, operated by La Clínica de la Raza.

Hernandez and Ortega said most of the people they know are eager to sign up for Medi-Cal but don’t know where to start. Many do not speak English, have limited literacy, and struggle to use or access a computer. The forms are available in 12 languages, but users may not find their language, such as the indigenous Mayan language Mam.

“The system seems friendly if you have a lot of experience using a computer,” Ortega said, but that’s not the case for most of the older adults he helps. “They come here and we have to fix everything.”

Californians without legal status make up the majority of the state’s uninsured residents, an estimated 3 million, according to the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

To get more of them covered, state legislators have expanded Medi-Cal to immigrants living in California without papers, rolling out the coverage in stages: first, to children in 2016; in 2020 to young adults up to 26 years of age, and to seniors last year.

Next year, full Medi-Cal coverage will be available to all qualifying Californians, regardless of age or immigration status. When this happens, they are expected to enroll close to 700,000 additional people from 26 to 49 years old, who are not citizens, according to the Governor Gavin Newsom’s Office.

Among all the changes, the expansion of the program to the elderly may have been the most far-reaching. Not only do they tend to need more care, but they are also more likely to have chronic conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes. Many do not seek health care or social services on a regular basis, a trend that has increased with the pandemic.

California will be the first state to expand Medicaid coverage to all immigrants. Illinois and Oregon have also expanded state-funded coverage to immigrant seniors, and New York plans to do so in 2024.

Although Medicaid is a joint federal-state program, for people without legal status, the federal government steps in only for emergency and pregnancy-related coverage. This means California taxpayers pay most of the cost of providing coverage, estimated at $878 million for immigrant seniors the first year, according to state budget officials.

When the expansion for seniors launched in May, those 50 and older who were already enrolled in the limited form of Medi-Cal were automatically transferred to the full version, which offers medical, dental, vision, and care long-term at no cost to most members.

Some Bay Area counties, including Alameda, Contra Costa and San Francisco, had an advantage in identifying eligible people because they administer health care programs for residents without legal status.

In recent months, community health advocates have focused on finding eligible seniors who haven’t heard of the expansion yet. Some have appeared on local television and radio news programs to get the word out.

“We know there are more who are eligible but not enrolled, Seciah Aquino said; Interim Executive Director of the Latino Coalition for a Healthy California. “We are working to make sure the numbers can continue to grow and that everyone who now has the privilege of accessing this benefit can sign up.”

A focus group study last summer, funded by the California Health Care Foundation, found that about half of the Hispanic respondents had not heard of the change. An even smaller proportion of older immigrant Asians knew this. Asians make up the second largest immigrant group in California after Hispanics, who account for nearly 40% of immigrants in the state. (California Healthline is an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation).

Some of the people who remain unregistered are hard to persuade because they fear revealing their immigration status to a government program, community health workers report. Medi-Cal applicants must disclose their status on the application, but state officials say the law requires that the information be kept private, and not shared with immigration authorities.

Those assurances are often met with skepticism.

Many eligible seniors point to the Trump administration’s “public charge” policy, which made Medicaid enrollment a possible reason to be denied legal residence in the country. Although that policy it was revoked in decemberthe fear persists.

Embriz, which had limited Medi-Cal coverage for many years, said it dropped in 2020 due to public charge. He didn’t want his enrollment in Medi-Cal to ruin his chances of getting a green card. But once he learned that registering wouldn’t affect his green card application, he agreed.

“It would make a world of difference,” Embriz said of getting routine checkups again. “I have high hopes.”

For some older immigrants who have signed up, the ability to get full coverage has been a godsend. Maria Rodríguez, 56, of Hayward, learned in September that she was eligible while visiting the Tiburcio Vásquez Health Center, a local clinic that treats uninsured patients. A social worker helped her complete the online application after a doctor diagnosed her with high blood pressure and diabetes.

“It’s like Medi-Cal fell out of the blue,” Rodriguez said. “It is very beneficial for my health.”

Claudia Boyd-Barrett is a reporter for California Health Report. This article has been produced in collaboration with California HealthlineCalifornia Health Report y the eardrum.

Low-income California residents age 50 and older can apply for all Medi-Cal benefits, regardless of immigration status. Here are some ways to apply:

Covered California: https://www.coveredca.com. At the bottom of this page you will find translations available in several languages. To communicate by phone, call 800-300-1506 to be attended in English, or 800-300-0213 to speak with an operator in Spanish. The forms to apply for Medi-Cal are available in 12 languages, ready to print.

Mail the completed and signed form to:

Covered California

P.O. Box 989725

West Sacramento, CA 95798-9725

CalWIN: https://www.mybenefitscalwin.org. This webpage is available for residents of 18 counties to apply for public benefits from various programs; the list includes Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, Solano and Sonoma counties.

To find other social service agencies by county:

HealthyAC: https://healthyac.org. For Alameda County residents only. This website includes a list of organizations, sorted by ZIP code, that offer assistance with the application process. Call 510-272-3663 to process your registration over the phone or to request an application form.

house CHE: Managed by La Clínica de la Raza (https://laclinica.org/), Casa Che provides assistance with enrolling in health insurance in Alameda, Contra Costa and Solano counties. Call 855-494-4658 to schedule an appointment.

This story was produced byKHNwhich publishesCalifornia Healthlinean editorially independent service of theCalifornia Health Care Foundation.

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here