How did science get started? A few years back, we looked at one answer to that question in the form of a book called The Invention of Science. In it, British historian David Wootton places the origin within a few centuries of European history in which the features of modern science—experiments, models and laws, peer review—were gradually aggregated into a formal process of organized discovery.

But that answer is exquisitely sensitive to how science is defined. A huge range of cultures engaged in organized observations of the natural world and tried to identify patterns in what they saw. In a recent book called Horizons, James Poskett places these efforts firmly within the realm of science and arrives at his subtitle: “The global origins of modern science.” He de-emphasizes the role of Europe and directly dismisses Wootton’s book via footnote in the process.

Whether you find Poskett’s broad definition of science compelling will go a long way to explain how you feel about the first third of the book. The remaining two-thirds, however, are a welcome reminder that, wherever it may have started, science quickly grew into an international effort and matured in conversation with international cultural trends like colonialism, nationalism, and Cold War ideologies.

Thinking broadly

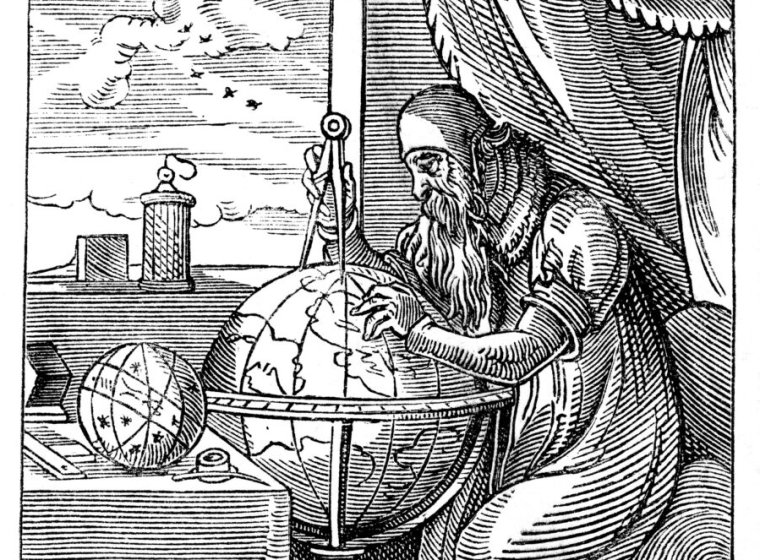

Poskett waits all of one paragraph before declaring it a “myth” that science’s origin involved figures like Copernicus and Galileo. Instead, he places it not so much elsewhere as nearly everywhere—in astronomical observatories along the Silk Road and in Arabic countries, in catalogs of Western Hemisphere plants by the Aztecs, and in other efforts that were made to record what people had seen of the natural world.

Some of those efforts, as Poskett makes clear, required the organized production of information that we see in modern science. Early astronomical observatories boosted accuracy by constructing enormous buildings structured to enable the measurement of the position of heavenly bodies—hugely expensive projects that often required some form of royal patronage. Records were kept over time and were disseminated to other countries and cultures, another commonality with modern science. Some of this activity dates back all the way to Babylon.

Yet all this information production is still missing some things that are commonly seen as central to science. Astronomers in many countries figured out ways of calculating the patterns in the movements of planets and timing of eclipses. But there’s little indication that any of them recognized that those patterns reflected a small number of underlying principles or that their predictions could be improved by creating a mental picture of what was happening in the heavens. Without things like models and laws to pair with the observations they explain, can we really call this science?

Poskett’s answer would be a decisive yes, though there’s no indication in this book that he ever considered that a question in the first place. In fact, his definition of science is even broader (and probably on even weaker ground) when he refers to things like an Aztec herbalism manual as science. Is there any evidence that the herbs it described were effective against the maladies they were used to treat? Finding that out is definitely something science could do. Yet it would require scientific staples like experiments and controls, and there is no indication that the Aztecs ever considered those approaches. Poskett’s choice of using it as an example seems to highlight how organized knowledge on its own isn’t enough to qualify as science.

A full perspective on the origin of science will necessarily recognize that many non-European cultures had developed better observations and more sophisticated math centuries before figures like Galileo and Copernicus and that access to these observations was critical to the eventual development of what we now recognize as science. But a compelling argument can be made that these alone aren’t sufficient to be called science. It would have been interesting to read an equally compelling counter-argument. But in Horizons, Poskett doesn’t even try to formulate one—he simply declares all of this science by fiat.

(I’ll note that, by the more stringent definition, even figures like Copernicus weren’t actually doing science, even though they made critical contributions to it. Copernicus lacked any mechanism to explain the motions of the planets in his heliocentric model and was remarkably vague about whether he thought that model was in any way reflective of reality. So someone with a stringent view of what constitutes science would probably agree with Poskett that describing Copernicus as one of the first scientists is a myth. They’d just do so for very different reasons.)

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25257619/3b67ad95d86eed9123b3b4a8cc7e6ad1fb5dbb51dc126bbbda89a1ac2f172b81.jpg)