Clams called Heart cockles, found in the warm, equatorial waters of the Indo-Pacific, have a mutually beneficial relationship with microscopic algae living in their tissues. The algae need light to thrive, and in return, the clams benefit from the sugars produced by the algae through photosynthesis.

To support this bond, heart cockles have evolved natural skylights in their shells, directing light to their dark interiors without opening their shells. This clever adaptation allows the clams to fuel the growth of their algal companions while avoiding exposure to predators.

A new study- by researchers from Duke University and Stanford University- reveals that heart cockles, named for their heart-shaped shells, possess unique structures in their shells that function like fiber optic cables, channeling specific wavelengths of light into their tissues.

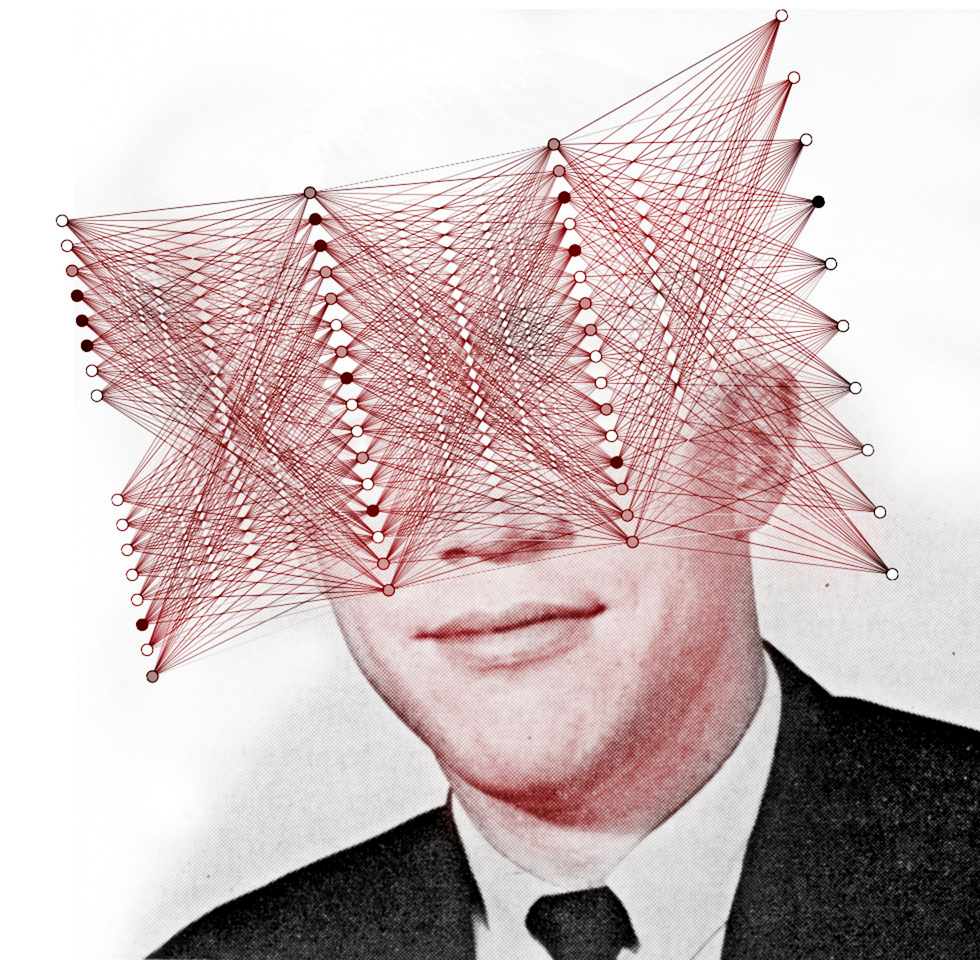

Researchers used electron and laser microscopy, along with computer simulations, to discover that the translucent areas of the cockles’ shells contain hair-thin strands arranged in bundles, which deliver light deep into the bivalve’s tissues.

Giant clams may be the most efficient solar energy system

Using a laser scanning microscope to study the 3D structure of heart cockle shells, researchers discovered that beneath each translucent window, tiny bumps smaller than a grain of sand act as lenses. These bumps concentrate sunlight into a beam that penetrates into the clam’s interior, providing the light needed for the algae living inside to thrive.

Sönke Johnsen at Duke said, “I imagine it like some organic cathedral with stained glass windows, with the light falling on the parishioners inside.”

First author Dakota McCoy said, “After looking at the shells under a scanning microscope, we were surprised to know- Heart cockles and many other marine animals use a special form of calcium carbonate called aragonite to make their shells. Under a microscope, most of the heart cockle’s shell has a layered structure, with thin plates of aragonite stacked in different orientations, “kind of like fancy brickwork.”

Optical fibers that can “feel” the materials around them

Within each window of the heart cockle’s shell, the material forms tightly packed, hairlike fibers, rather than plates, all aligned with the direction of incoming light. Computer simulations revealed that the size, shape, and orientation of these fibers are optimized to transmit more light into the clam’s interior compared to other potential designs.

Specifically, they allow light in the blue and red ranges, which are ideal for photosynthesis, while blocking harmful ultraviolet radiation that could damage the clam’s DNA.

Johnsen said, “Together, the fibers and the lenses create a system for filtering out bad wavelengths, channeling in the good wavelengths, and focusing so that they go far enough into the shell, so that the algal symbionts get the best lighting environment possible.”

The researchers also discovered that the tiny, tightly packed fibers in the heart cockle shells create a high-resolution image of whatever is beneath them when light is shone through. This projection ability is almost like a TV screen.

While more research is needed to understand if the heart cockles use this “image projection” in any way, the team believes these findings could inspire new designs for fiber optic cables that allow light to travel long distances, even around curves, without losing signal. As McCoy noted, the shells perform a remarkable feat.

Journal Reference:

- Dakota E. McCoy, Dale H. Burns, Elissa Klopfer et al. Heart Cockle Shells Transmit Sunlight to Photosymbiotic Algae Using Bundled Fiber Optic Cables and Condensing Lenses. Nature Communications, Nov. 19, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-53110-x

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here