Nestled on the eastern ridge of the Colombian Andes, some 150 miles from Bogotá, sits Lake Tota, Colombia’s largest lake. Each week, hundreds of tourists flock to the lake’s shores to enjoy its serene waters, white sand beaches, high montane forests, and a cluster of restaurants specializing in rainbow trout. But beneath the placid stillness of the lake’s surface lurks an unsolved mystery: An unusual fish called the Fat Catfish, considered the lake’s only endemic fish species, has seemingly vanished.

The Fat Catfish (Rhizosomichthys totae) has not yet been officially declared extinct—whether any members of the species still remain in the lake, no one can say for sure, but the fish has been lost to science for nearly 70 years. Now a cadre of scientists has become obsessed with closing the case. If they can confirm that the fish is no more, it would be the first freshwater fish extinction recorded in all of South America in modern times.

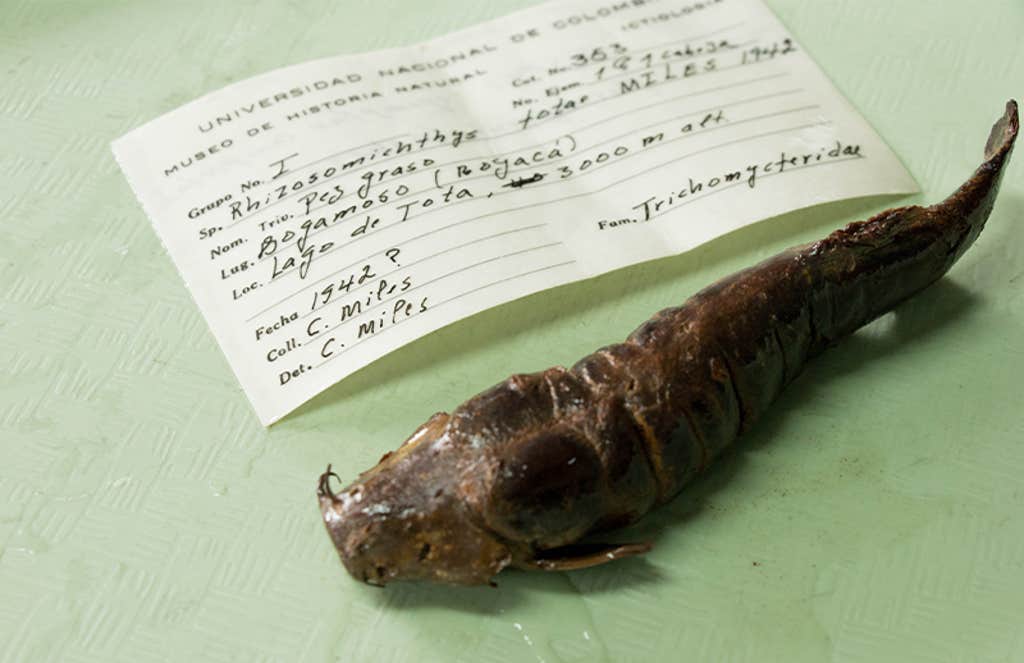

Colombians call the Fat Catfish pez graso or “grease fish,” perhaps because locals reportedly used its fat for fuel in oil lamps at the beginning of the 20th century. That is to say, the Fat Catfish is, in fact, fat. According to reports, the fish is about 5.5 inches in length, and its core is enveloped in six or seven rings of connective fat tissue, giving it the appearance of a Michelin Man with the head of a fish. Even before it vanished, the fish had reportedly only been sighted in Lake Tota, and nowhere else in the world.

The fish burns like a candle when either of its fins is ignited.

Carlos Lasso Alcalá, a researcher at Colombia’s Humboldt Institute, is one of the scientists who has become consumed by the hunt for the Fat Catfish. He is a leading freshwater fish expert in Colombia, with a passion for remote ecosystems, such as rivers in caves and unexplored parts of the Amazon. Lasso Alcalá coordinates the Fat Catfish search project, which launched in 2021 and is part of a campaign called Search for Lost Species, which is partially funded by actor Leonardo DiCaprio and organized by United States-based conservation group called Re:Wild, along with SHOAL, a United Kingdom-based NGO focused on freshwater fish protection.

The Search for Lost Species effort has a rotating list of 25 “most wanted” species in the world—everything from toads, beetles, moles, and fungi, to of course, the Fat Catfish. They are selected from a long list of 4,300 species across taxa and geographic distribution. To qualify for the long list, a species must have been lost to science for at least 10 years and no members of the species can live in captivity. Which species make it onto the priority list is relatively subjective, but these lost species are generally ones whose disappearance involves a compelling story, draws significant interest from local scientists and authorities, and has the potential to inspire concrete conservation action for an entire habitat. Each time a lost species is found again, a new one takes its place on the list. The campaign has so far managed to “re-discover” 13 “lost” species around the world, including the De Winton’s golden mole, Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna, and the big puma fungus.

The first written account of the Fat Catfish seems to have been recorded in 1942 by Cecil Miles, an English ichthyologist and a pioneer of commercial-scale fish farming in Colombia. Most everything we know today about the fish appears to come from Miles’ rather florid description of the fish, and the analysis of a mere 10 specimens he donated to museums in Colombia, the U.S., and the U.K. According to Miles, the fish could be easily distinguished from other catfish species by “its fatty rings, which resemble a series of automobile tires” and “by its repulsive appearance and buttery odor.” Miles theorized that the fatty rings provided insulation against the cold depths of Lake Tota—which features surface temperatures of between 32 and 54 degrees Fahrenheit—or perhaps served as a form of energy reserve. “This fat is easily combustible,” he wrote in his account, “and the fish burns like a candle when either of its fins is ignited.” He also observed that locals sometimes used the oil from the fish in lamps to light up their homes.

These days, hunting for rare, elusive, or lost species often entails borrowing a technique from the forensic sciences: collecting DNA samples from water, soil, air, or snow and then attempting to match these environmental DNA samples against ones kept in a bank for a given species. This way, scientists can detect the presence of an animal, plant, or fungus at a particular location without directly glimpsing the species in the flesh.

The problem with this method in the case of the Fat Catfish is that researchers have little information about its genetic blueprint: All the specimens are kept in formalin, which damages DNA, says Susana Caballero Gaitán, an associate professor at the University of the Andes in Colombia, who specializes in conservation genetics. She is also in charge of the environmental DNA analysis in the Fat Catfish search project.

The workarounds, says Caballero Gaitán, are labor intensive. “What we have to do is like a process of elimination.” The scientists collect water samples from the lake and eliminate the DNA of all identifiable fish species one by one, hoping to find an anomalous sample that is similar to that of the Fat Catfish’s closest relative, the capitán de la Sabana fish (Eremophilus mutisii). The capitán de la Sabana fish belongs to the same taxonomic subfamily as the Fat Catfish, has similar physical features and is endemic to the region. (Though it is common in Lake Tota, it is not native to the lake. It was introduced to the lake by humans.) All these similarities suggest that the two fish are evolutionarily close and probably share some DNA as well. If the researchers could find such samples, it would be the first concrete sign of hope that the Fat Catfish might not have been lost forever.

The fish could be distinguished from other catfish by “its fatty rings, which resemble a series of automobile tires.”

The lake is large—some 34 square miles in surface area, and more than 164 feet in depth—so in 2023 and 2024, the team sent divers to sample various spots along the shore and at different depths. As of November 2024, the scientists have not found any bits of DNA that could belong to Fat Catfish, but they did detect an “unspecified fish” in one of the samples. There is a remote possibility it could be linked to the Fat Catfish, but researchers are still working out what this genetic sample could mean for the search.

Diving to search for this microscopic evidence at the altitude of Lake Tota is no simple matter: Its dazzling waters lie nearly 10,000 feet above sea level. It’s dark and cold, and at greater altitudes, the atmospheric pressure is lower. This means that decompression sickness—a serious condition when nitrogen bubbles form in the bloodstream if a diver ascends too quickly from depth—can occur more easily. Visibility in Lake Tota is also low thanks to muddy sediments, so divers often see less than 10 feet ahead.

Luis Fernando Barrios, biologist and scientific diver at the Colombian Federation of Underwater Activities, together with Lasso Alcalá and other divers, spent a week in 2023, and another week in 2024, collecting samples from the shores where tributaries meet the lake and from the lake itself at depths down to 82 feet. The divers were armed with underwater cameras and headlamps so they could also conduct a good, old-fashioned visual hunt for the fish. They came up empty: No Fat Catfish, no sure-thing DNA.

From there, the team pivoted to historical research. They took a deep dive into local records, maps, Indigenous legends, and even paintings and illustrations related to the lake from as early as the 16th century, to see if any clues about the fish would rise to the surface.

Lake Tota has been a sacred place for the Indigenous Muisca peoples since well before the Spanish conquest of Colombia in the 16th century, says Mariana Moscoso Rodríguez, an anthropologist and journalist of Ictiología y Cultura, a social research group in charge of the anthropological and sociological efforts of the Fat Catfish search. The Muisca have passed down legends about sacred animals that lived in the lake, including a monstrous fish that had an ox-like black head and was bigger than a whale. This myth largely scared local people away from fishing in the lake until the turn of the 20th century, when it was fully mapped and the Colombian government began looking into possibilities for economic development. But the team turned up no Muisca legends or even rumors about a catfish with puffy rolls of fat.

Moscoso Rodríguez and her team spent weeks in 2022 interviewing local communities about their memories of the fish around Lake Tota and its tributaries. “We asked very old ladies, like 90-year-old grandmothers, and it was a very visual search because we showed them photographs,” she says. “It’s crazy because if Indigenous people lit their torches with the fat from the fish … this would be in peoples’ memory.”

Rodríguez and her colleagues decided it was time to fact-check Miles’ description of the fish—and they found some irregularities. For example, he claimed in his account that an earthquake “a few years before” 1942 killed “a large number” of Fat Catfish and left them floating on the surface of the lake. After checking the Colombian Geological Service’s archives, Moscoso Rodríguez found no significant seismic activities recorded in the region during that period of time.

Did Miles ever really see the fish in Lake Tota? Did it come from somewhere else? “It’s very possible that someone, an Indigenous person or a farmer, brought this species to Miles either from the páramo or somewhere else,” says Rodriguez.

The lack of collective memory about the striking fish pushed the scientists to cast their net wider and map smaller waterbodies around the highlands of Lake Tota and to recommend additional DNA collection spots to the team for future expeditions.

Meanwhile, Lasso Alcalá found a speckle of evidence regarding the possible whereabouts of the Fat Catfish. “There is a piece of sand in the mouth of a [preserved] specimen that has nothing to do with Lake Tota,” he says. Geological analysis of the origins of this grain of evidence could push researchers in new directions in their search for the fish. Lasso Alcalá is also keen to give Miles’ fantastic earthquake claim another chance and carry out archaeological excavations around Lake Tota’s shore to look for possible preserved remains of Fat Catfish.

If the fish did once swim in Lake Tota, Miles may have been the one to spell its doom: He helped establish the first trout farm at the lake in 1939. One prominent theory about the reasons behind the disappearance of the species is the introduction of these rainbow trout into Lake Tota. This larger trout preys on other fish, and as the lake’s only known potential endemic fish, the Fat Catfish might have been on its menu. Alternatively, it might have been crowded out of its habitat by the other fish species introduced to the lake as food for the trout.

For now, the mystery endures. The results of the search remain inconclusive but the team is not giving up, says Lasso Alaclá. “We are handling many hypotheses. This story is not over yet.” ![]()

Lead image: Apokryltaros / Wikimedia Commons

Kata Karáth

Posted on

Kata Karáth is a freelance journalist and documentary filmmaker. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Science Magazine, Quartz, and New Scientist, among others. She is based in Ecuador.

Published in partnership with:

Get the Nautilus newsletter

Cutting-edge science, unraveled by the very brightest living thinkers.

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here