A new immersive visitor center sheds light on Céide Fields, an archaeological site older than Egypt’s Pyramids.

Published September 7, 2022

9 min read

Flanked by dramatic cliffs and the Atlantic Ocean, a five-square-mile stretch of bogland in County Mayo blankets a field between Ballycastle and Belmullet in west Ireland. With few trees and low hills, it looks empty, but on this isolated shore lies one of Ireland’s greatest archaeological finds.

Several bogs in Ireland have revealed glimpses of societies long past. Treasures found have included religious chalices, hordes of gold, a medieval psalter, 2,000-year-old “bog butter” (chunks of butter made from milk fat and buried in the bog to preserve it), and “bog bodies” (preserved human remains, such as Cashel Man, the oldest found bog body, which dates to 2000 B.C.).

But it wasn’t until the 1930s when a schoolteacher from Belderrig, Ireland, was cutting peat for fuel that the first remains of the largest Neolithic site in Ireland were revealed. The discovery led researchers to uncover some of the oldest known stone-walled fields in the world, dating from about 3800 B.C.—older than the pyramids of Egypt (2550 B.C.) and Stonehenge (3500 B.C.).

Known as Céide Fields—or Achaidh Chéide, meaning “flat-topped hill fields”—the site may not be as famous as the Burren, but a new immersive visitor experience, opened in June, might change that. At this tentative UNESCO World Heritage site, interactive exhibits delve into the history of the walls, the ancient farming fields they enclosed, and what we can still learn about the people who lived there.

Bog treasures

Millennia of decaying plant matter and waterlogged soil slowly erased any proof that Céide Fields existed until schoolteacher Patrick Caulfield, who was out on the bog cutting peat (removing and drying turf to burn for fuel), came across large stones piled in long lines deep within the muck. He wrote to the National Museum in Dublin in 1934 to alert them of his discovery. Even though they regarded the find as significant, the museum did not have the resources at the time to investigate.

Nearly three decades later, in 1963, a team of archaeologists, led by Patrick’s son, Seamus, used traditional iron probes—normally employed for finding fallen trees under areas of deep bog—to search the land. The team unearthed foundations for domestic dwellings, Neolithic tools like scrapers and arrowheads, and acres of collapsed walls. Carbon dating later proved the site existed nearly 6,000 years ago, revealing an organized, agricultural community developed the land.

“In terms of early farm landscapes, [Céide Fields] is an outstanding example at a global level,” says Gabriel Cooney, emeritus professor of Celtic archaeology at University College Dublin. “It provides us with evidence of the interaction of people with their environment. It’s critical to our understanding of farming and how it happened and the context in which it happened across the world.”

Patrick’s grandson, Declan Caulfield, continues the family’s legacy at his company, Belderrig Valley Experience. He leads private two-hour to two-day excursions around the bogland where the walls were first found. During the tours, visitors grind grain using ancient quern stones, discover how local grains were milled, and learn how buildings were made using stone and wood.

“My grandfather had the insight into something very ancient. I think [his discovery] is an important part of the story to tell,” Declan says.

Guiding me through patches of tiny pink bell heather and yellow potentilla (rare finds in this oxygen- and nutrient-poor wetland), Declan explains how Irish myth and scientific discoveries can often intertwine, sometimes unknowingly creating sacred spaces.

For decades locals and farmers had avoided a stone circle in the area due to superstition that it was a fairy ring or fairy fort that might bring bad luck if tampered with. Archaeological excavations would go on to reveal that this “fairy fort” was a Bronze Age round house, which was built with stones from the original Céide Fields development.

(Venture inside the Irish ‘hell caves’ where Halloween was born.)

Probing the bog

While parts of Céide Fields have been excavated, there are still hundreds of acres of history submerged under bogland that may never be explored. “We know there is a huge amount of material that is still out there,” says Gretta Byrne, an archaeologist who joined the Céide Fields excavation team in 1981 as a student and now manages the visitor center. “[But] a lot of it will stay out there. You just couldn’t possibly investigate every inch of that. We’d be here for another 5,000 years.”

Still, travelers can attempt to solve the mysteries of the people who lived and farmed on the land at the newly renovated, $2.6 million immersive visitor center, a lesser known stop on the 1,600-mile Wild Atlantic Way, one of the longest defined coastal routes in the world.

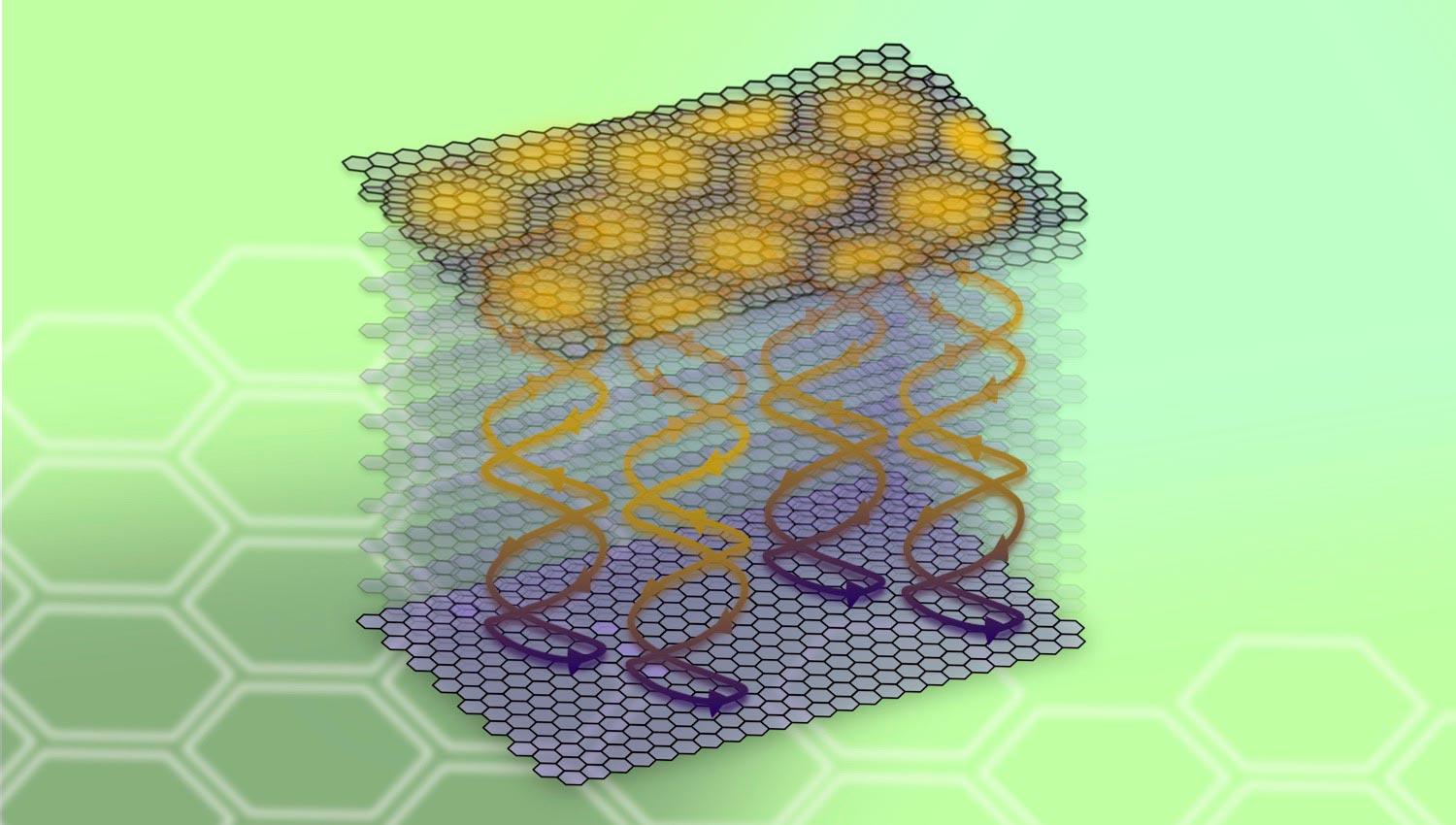

With state-of-the-art audio-visual exhibits, artist reconstructions, and an observation deck offering sweeping views of the sea-cliff landscape, the center gives visitors a deeper understanding of Stone Age Ireland. Replicas of log boats show how the first farmers arrived in Ireland, illustrations depict how the woodlands dominated by pine and birch were cleared to build dwelling houses and enclosures for livestock, and interactive displays describe how the farmers erected stone monuments to commemorate the dead.

Roberta Richiero, a tourist from Turin, Italy, says that visiting the center is “like being on the edge of both time and space because you are on the cliffs [which] is like the ‘end’ of the world, and at the same time you step back into history, like the beginning of the world.”

(These archaeological findings unlocked the stories of our ancestors.)

To give further insight into how vast the site is, Byrne leads guided tours through the bog, explaining the geography, ecology, and importance of rain in the area. “You need 50 inches of rain around 225 days of the year to form blanket bog,” she says. “We get rain on about 250 days.”

Walking over soft peat, Byrne guides me to sections of the bog where the turf has been cut away to show how deep archaeologists had to dig to unearth the walls. One section shows where the ground would have been when the farmers started building and then how the bog rose more than 13 feet over the settlement. After a brief demonstration from Byrne, visitors are invited to use iron rods like the ones the researchers used to make their own discoveries.

Despite there being much more to explore, Byrne says it’s good that a lot of Céide Fields remains untouched. “With excavation, once you remove the soil from the ground, that bit of soil is essentially destroyed, but in the future, there may be new techniques we can’t even dream of now,” she says. “That’s the thing about archaeology, there are new discoveries being made all the time.”

Yvonne Gordon is an award-winning travel writer and photographer from Dublin, Ireland. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here