“Capitalists both in the Old World and the States, even now, have but little faith in California. They regard this country and everything relating to it as one grand bubble, liable to burst at any moment…. This is how it should be. The wealth of California is thereby passing into the hands of young, active, enterprising men, who in an older country and with these same old capitalists as competitors might have worked to the end of their days, and realized but a mere pittance.” — San Francisco Daily Journal of Commerce, 1850

“It is as though an immense wedge were being forced, not underneath society, but through society. Those who are above the point of separation are elevated, but those who are below are crushed down.” — Henry George, Progress and Poverty, 1879

In my mid-20s at the very bottom of the last economic cycle, I moved back to the San Francisco Bay Area in 2009.

Several months earlier, I had gone into work in at 6 a.m. in London’s banking district to write about global debt and short-term money markets when an 158-year-old Wall Street institution, Lehman Brothers, had filed for the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history.

It was a moment of financial paralysis unlike any other in recent American economic memory. A month later in Silicon Valley, the legendary venture capital firm, Sequoia Capital, circulated its now famous R.I.P. deck, warning founders throughout the industry to clamp down on spending or face imminent failure.

When I returned home, you could get a room for $800 on Dolores Street. After living in New York City and London, it was the cheapest housing I had ever found.

At that time, the region’s technology industry was still somewhat chastened by the dot-com bust less than a decade before, and it wasn’t as hard to hunt for vestiges of a cyberpunk or freak culture that I remember from the mid-1990s as a teenager.

I was hopeful about it. Young people were flocking into San Francisco from all over the country and world, and it was still inexpensive enough that you could experiment and explore.

But as we all know, less than five years later, everything changed. Silicon Valley’s center of gravity moved north from Palo Alto to SOMA. There was Rebecca Solnit’s Google Bus screed in the London Review of Books, and then the actual protests themselves.

Every day, I get messages.

A protest at the eviction of an African-American pastor, whose house had been sold by his bank after the foreclosure crisis. A white female entrepreneur expressing guilt about buying a home in the Bayview District, because it was the only place in the city that was affordable to her. One of the iconic Mission muralist non-profits looking to raise $200,000 in a matter of weeks as a down payment on the building they’re housed in, lest it gets sold to an owner that will presumably evict them. A handful of tech entrepreneurs of color in Oakland trying to set a respectful, inclusive culture before Uber moves in. Friends who are social workers, and then even highly-paid lawyers or doctors moving out of the region because they can’t see a long-term future here.

It’s just constant.

When the iconic Californian writer Joan Didion left New York for Los Angeles after the age of 28, she wrote, “One of the mixed blessings of being twenty and twenty-one and even twenty-three is the conviction that nothing like this, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, has ever happened to anyone before.”

Of course, nothing like this has ever happened before.

Almost one hundred fifty years ago in 1858, a nineteen-year-old arrived in San Francisco after a five-month stint as a steward on ship crossing South America’s Cape Horn from Philadelphia. After staying with a cousin, this young man, Henry George, would eventually take up residence in the Mission District.

Almost one hundred fifty years ago in 1858, a nineteen-year-old arrived in San Francisco after a five-month stint as a steward on ship crossing South America’s Cape Horn from Philadelphia. After staying with a cousin, this young man, Henry George, would eventually take up residence in the Mission District.

It was a few years after the Gold Rush had ended, but just the beginning of a new railroad boom. An indecisive, young man, George tried his hand at being a printer, a farm laborer and a weigher at a rice mill, according to historian Edward T O’Donnell’s new biography, “Henry George and the Crisis of Inequality.” (I crib lots of details from O’Donnell’s work in this piece, so if you like it, you should just buy his book).

George eventually settled into printing and typesetting, although stable employment was always a remote reality for him.

By 1865, his floundering printing business had brought him to the brink of starvation. With an eight-month pregnant wife who had pawned everything but her wedding ring, the situation became hopeless. On the day that she gave birth, he stepped out into the rain to beg for money.

“I stopped a man — a stranger — and told him I wanted $5. He asked what I wanted it for. I told him that my wife was confined and that I had nothing to give her to eat. He gave me the money. If he had not, I think I was desperate enough to have killed him.

That deeply personal experience with poverty left a mark on George for the rest of his life. He would always remember what this feeling of absolute want was like.

Over the years, he became vocal as an editor on issues of the day like the construction of the railroads. The year before Leland Stanford drove the golden spike into the railroads connecting the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans at Promontory, Utah, George wrote an essay on the promises and drawbacks of the new transportation technology.

On the one hand, he saw San Francisco rising to the rank of a single, world-class metropolis encircling the entire Bay Area:

Is it too much to say that this city of ours must become the first city of the continent; and is it too much to say that the first city of the continent must ultimately be the first city of the world? And when we remember the irresistible tendency of modern times to concentration — remember that New York, Paris and London are still growing faster than ever — where shall we set bounds to the future population and wealth of San Francisco; where find a parallel for the city which a century hence will surround this bay?

And yet, on the other, George saw that the railroad’s benefits would only advantage a few. Stanford and the other members of Central Pacific’s Big Four, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker, initially had problems constructing the railroad profitably. After securing favorable financing terms from the U.S. federal government and about two years of work, they had only managed to lay out 50 miles of track. But once they turned to inexpensive Chinese-American laborers, who were willing to work for two-thirds of the price of European crews, they were able to blast through technically difficult passes like Bloomer Cut near Sacramento.

It was somewhat ironic, given that just a few years earlier, Stanford had called Chinese-Americans “a degraded and distinct people” in his inaugural speech as California governor and urged limits on immigration from the continent. Stanford later changed his mind, and wrote to U.S. President Andrew Johnson that without the Chinese, the Transcontinental Railroad would not have been possible, and that they were “quiet, peaceable, patient, industrious and economical” people.

Transportation and communications technologies like the railroads and the telegraph would truly integrate the U.S. economy from coast-to-coast for the first time, and give rise to a new industrialist and banking class that would supersede the merchant class in cities like New York and San Francisco.

George noted that while these new industrialists and land owners would benefit, many others would have to struggle harder:

“Those who have lands, mines, established businesses, special abilities of certain kinds, will become richer for it and find increased opportunities; those who have only their own labor will become poorer, and find it harder to get ahead — first, because it will take more capital to buy land or to get into business; and second, because as competition reduces the wages of labor, this capital will be harder for them to obtain.”

This issue of land, and land engrossment, would become one of the most heated issues of the period. Large-scale farming operations and industrial cattle ranchers like Miller & Lux were manipulating the judicial system in the wake of the Mexican-American War to wrest control of large tracts of land from Mexican owners. By early 1870s, a mere 100 owners controlled 5.4 million acres in California, an area slightly larger than the state of Massachusetts.

One afternoon around that time, George was riding a horse in the Oakland Hills and stopped to ask a passing teamster about the value of the nearby land. The teamster had no idea, but replied that another owner was selling land at $1,000 an acre.

“Like a flash it came upon me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay for the privilege. I turned back amidst quiet thought, to the perception that then came to me and has been with me ever since.”

Land would become George’s defining issue. His argument was that land defined the business cycle, not the other way around. Speculators would increase the price of land faster than wealth could be created to pay for it, leaving less left over for labor to earn as wages. The land and housing boom would finally become so unsustainable, that it would lead to a collapse of enterprises at the margin, prompting a recession or depression with widespread unemployment.

He called land an “immense wedge.” Those with the right to it were “elevated,” while those without it, were “crushed down.”

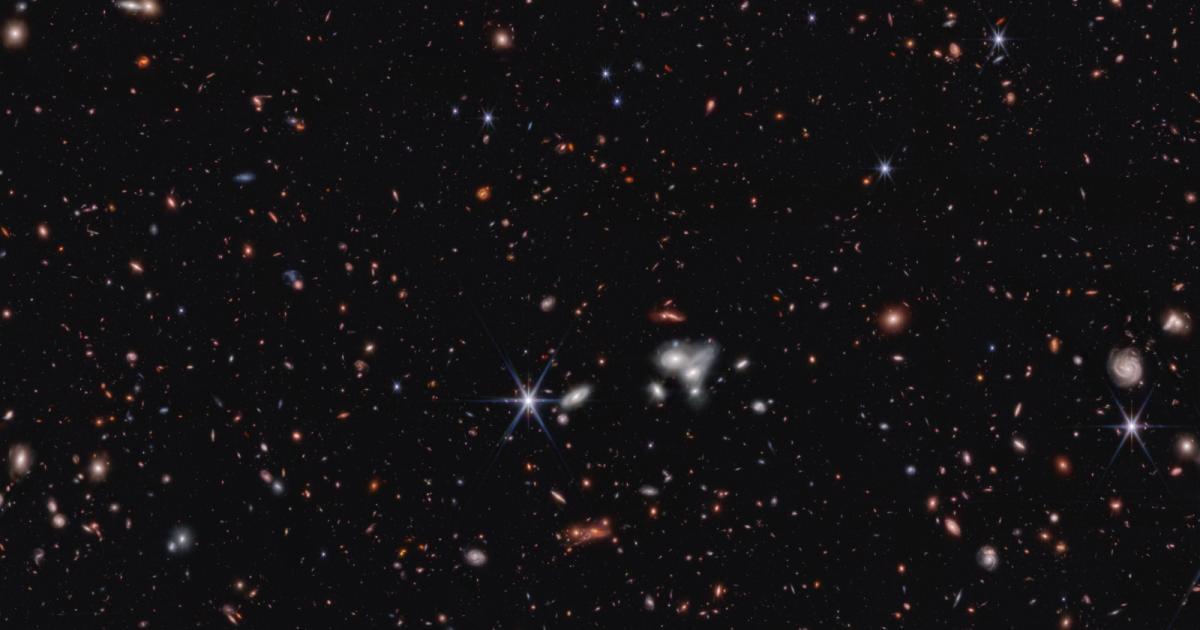

The wedge is obvious today. San Francisco Bay Area poverty rates in all nine counties have increased in the last economic cycle, even with the Facebook and Twitter IPOs and private tech boom. The main transfer mechanism is land and housing costs, as rising rents and evictions push service and other low-wage workers to the brink.

George’s solution was a single land tax that would replace all other government revenue sources. If an owner wanted to develop their property to make it more useful or productive, George argued that they should have the right to keep the value from those efforts. But increases in the value of underlying land were created by — and ultimately belonged to — the public at large.

Because no one could create land, it would be impossible to tax it out of existence. In contrast, property taxes disincentivize people from using land more productively, since re-developing land leads to higher re-assessments. A century later, Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz would prove out a Henry George theorem, showing that in certain cases increased investment in public goods boosted land rents by at least that much. This suggests that land taxes alone could be enough to sustain public or government expenditures. Milton Friedman would call them the “least bad tax,” while Karl Marx called George’s ideas “capitalist’s last ditch” with a hint of friendly contempt.

George would publish these ideas in his seminal work “Progress and Poverty,” which would go on to sell several million copies and kick off the Progressive Era.

“Progress and Poverty” captured the zeitgeist of the times. The parallels between the late 19th century Gilded Age, named after a Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner novel about a speculative land deal gone awry, and the modern era are striking.

In the 1870s, there were just 100 millionaires in the United States. But by 1892, the New York Tribune counted 4,047, and by 1916, there were more than 40,000. At least two, John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and Henry Ford, were billionaires.

But that prosperity was not equally shared. During the next two decades, the U.S. economy would lurch from crisis to crisis, as the country’s manufacturing workers outnumbered the agricultural labor force for the very first time in American history. Cities like New York City and Chicago saw their populations explode, as the country’s urban share of the population rocketed from 6 to 40 percent between 1800 and 1900.

A sustained five-year contraction in the 1870s would put 54,000 businesses, 5,000 banks and half the country’s railroads out of business, with unemployment skyrocketing to 30 percent. Because there were no body of tenants’ rights laws at the time, evictions in Gilded Age New York grew from 16,000 per year in the early 1880s to more than 23,000 by 1892.

The Ubers of the day, New York’s streetcar corporations, were powerful and profitable, but their workers suffered immensely. During a mid-1880s national campaign for an eight-hour workday, streetcar drivers and conductors worked between fourteen and sixteen hours per day, usually without breaks, and standing the entire time on platforms exposed to all of the elements, whether in the searing heat or biting cold. The streetcar companies routinely deducted “fines” from their drivers’ pay for minor offenses, not unlike the way that ride-hailing networks have routinely reduced their drivers’ take home pay per ride regularly over the last few years.

Just a few decades after Alexis de Tocqueville had praised the U.S. as an egalitarian land without extremes in “Democracy in America,” the urban elite of cities like New York were left with a discomfiting realization that American exceptionalism was perhaps ending and giving way to a large working proletariat that could radicalize or rebel like in Europe.

The urban elite backed the construction of armories, like the one in San Francisco’s Mission District that’s currently used to film kink and sado-masochistic pornography or the one in New York used annually for the high-end contemporary art fair, The Armory Show, to protect their assets and property in the event of labor riots.

Into this period of enormous technological and economic change and societal stress, George’s book, “Progress and Poverty,” shot him into the public consciousness. He would eventually run for mayor of New York City, beating future U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt but ultimately losing to a Tammany Hall candidate.

Four days before his next run at mayor of New York City, George died of a stroke. His idea for a land tax was never implemented, but the Progressive Era he kickstarted fundamentally changed the nature and shape of the U.S. government.

Around the time that George published “Progress and Poverty,” the U.S. had the smallish sort of government that modern-day libertarians would favor. It took in less than 2 percent of GDP in taxes through customs revenues and excise taxes, and most true governance happened at the local and state levels. There was no Federal Reserve Bank, the economy ran on the gold standard and military was small with only commitments to guarding the frontier. It was also deeply corrupt and patrimonial with private interests coursing through it using bribes and patronage.

But by the turn of the century, the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era that it kicked off, that government had been transformed from a small, clientelistic one that awarded positions on the basis of patronage into a much larger professionalized and merit-based bureaucracy, according to Francis Fukuyama’s Political Order and Political Decay.

Technological and economic changes had fundamentally altered the structure of society, creating demand for a new form of political governance.

This is part of the argument that underpins the work of economist Carlota Perez, whose work is sometimes cited by venture capitalists like Marc Andreessen, Chris Dixon or Union Square Ventures’ Fred Wilson.

She mapped out five technological revolutions across more than 200 years from the Industrial Revolution started in Northern England all the way through the beginnings of Silicon Valley in 1970s.

The most often-quoted part of her work focuses on how technology is adopted on an S-curve, with multiple phases. First, there is an installation phase with enormous, unstable speculative energy and then a crash.

After the crash, comes a turning point. Only then, can a broad-based deployment phase occur where a technology’s true effects on society are felt. This is the so-called Golden Age where the real money is made. The interpretation in Silicon Valley is usually that the 2000 to 2001 dot-com bust was the turning point, and that we’re now in the “Golden Age” for deployment of Internet-based technologies and businesses.

But Perez feels that Silicon Valley investors are misinterpreting her work.

In some lengthy e-mail correspondence I had with her last year, she argued that we were not in a Golden Age yet. She said we’re still at a turning point, and that the 2001 and 2008 crashes were a sort of double bubble.

“We are still in the turning point because finance continues to be decoupled from production,” she wrote me. “They are playing with derivatives and other synthetic instruments that are the equivalent of bets in Las Vegas. And they are still making money with them. The only ones that are really investing in innovation are the new giants of the ICT world, they are excited with their power and they feel like it’s deployment. It’s the shining bit of a very dark world, marked by inequality and hopelessness. When a golden age arrives, everybody knows it. You can feel prosperity reaching more and more people; there is hope for everyone, not just the successful few at the top.”

A missing piece of Perez’s work, that often goes underemphasized by the private investment community, is the role of government in creating an equitable framework that allows everyone to participate in benefits of technological change. This is not an argument in favor of big government for big government’s sake; it’s to point out that when technology changes the complexity or structure of society, citizens have to push public institutions to transform themselves too.

“Golden ages are not brought by markets alone,” Perez told me. “Historically, they have never done it.”

If Perez is right, the polarization and disillusionment obvious in the 2016 presidential primaries through the rise of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump is just the beginning of something else.

Broad institutional and governmental change is what the Gilded Age triggered in the ensuing Progressive Era. George’s ideas would echo for many decades and influenced an entire generation of leaders from Leo Tolstoy to Sun Yat Sen to George Bernard Shaw.

Even in California, his ideas lingered. Former San Francisco mayor and still active power broker Willie Brown tried to promote a Georgist land tax in the early 1970s before conservative homeowners voted in Proposition 13’s property tax caps. It’s funny because several hard-core SF progressives and even for-profit real estate developers in the city, have told me they’re fans of Georgist policies. (This is even though I have on occasion seen these exact same people in screaming matches with each other.)

So why was the land tax never implemented?

I would like to think that an even newer technology rendered George’s ideas obsolete — at least temporarily. Created about a decade after George’s death and paired with an unprecedented level of government infrastructural subsidy to support adoption, this technology unlocked a much bigger supply of inexpensive, greenfield land for development, enabled the formation of a broad-based, property-owning democracy and undercut the concentrated power of the urban land-owning class from the 19th century Gilded Age.

What was it?

The automobile.

Note: This article have been indexed to our site. We do not claim legitimacy, ownership or copyright of any of the content above. To see the article at original source Click Here